- Home

- Cooper, Lisa;

Britain and the Arab Middle East Page 4

Britain and the Arab Middle East Read online

Page 4

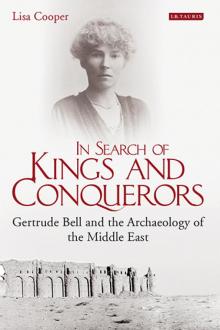

Fig. 1.1 Gertrude Bell, taken around 1895, when she was about 26 years old. By this time, Bell had already travelled widely and had published her first book, based on her impressions of Persia, visited in 1892.

While the Alps satisfied some of Bell’s physical needs, her emotional and mental capacities continued to be stimulated by travel, and she began looking farther afield, to exotic places that provided fresh landscapes upon which to marvel and peoples and cultures whose poetry, art and literature dazzled her in ways that were not satisfied by the confining, commonplace character of her native northern England. Her wanderlust is perhaps best expressed in her embarking on two world tours, in 1897–8 and 1902–3. The latter trip included a long stop in India, where she witnessed the imperial Durbar celebrating Edward VII’s accession to the throne as Emperor of India. Further stops included Singapore, China, Korea and Japan before she returned to England via Canada and the United States.11

Above all other places in the world, however, Bell seems to have felt the allure of the lands of the Near East, ignited by one of her earlier lengthy trips to Persia in 1892. Staying in Tehran with her aunt Mary and her uncle Frank Lascelles, the latter having been appointed British envoy to the Persian Shah,12 she found herself enchanted with the country around her, its breathtaking contrasts of mountains, deserts and gardens, fountains, silvery water streams and luxuriant roses. She also found its people hospitable and Persian art, music and poetry captivating. The sensations aroused within Bell in this exotic land were perhaps all the more keenly felt because she had fallen in love with a junior diplomat in the staff of the British Embassy in Tehran, Henry Cadogan. Their shared passion for poetry and literature, and the excitement of walking or riding together beyond Tehran to rapturously take in Persia’s impressive landscapes, only served to heighten and draw out Bell’s romantic nature. Sadly, Bell’s parents rejected Cagodan’s request to marry Bell – they considered him too poor and flawed in character to be an appropriate match. Compounding Bell’s bitter disappointment and grief, Cadogan died of pneumonia a year later, dashing any remaining hopes that he might have earned a promotion and thereby increased his eligibility in her parents’ eyes.13

Despite this grievous setback in Bell’s personal life, her love for Persia and the ‘East’ did not fade, and it may be that she hoped to hold on, as best she could, to the memory of Cadogan by immersing herself in all things associated with Persia and her sojourn there. Upon her return to England, she wrote of her Persian experiences with a ‘glowing eagerness’14 in her first book, Safar Nameh: Persian Pictures (London, 1894), and energetically studied the Persian language; after only a few short years, she completed a commendable English translation of the Poems from the Divan of Hafiz (London, 1897), which celebrates the verses of that great and highly revered fourteenth-century Persian poet.15

If Bell’s trip to Persia provided the first spark for her interest in the Near East, her subsequent journeys to the Levant around the turn of the century and in the years that followed consolidated a passion for the ‘East’ that would continue for the rest of her life. Each trip took her further off the beaten track, developing her self-reliance and resolve, testing her physical endurance and piquing her curiosity for new landscapes, peoples and built-spaces from the past and present. Bell’s first major Near Eastern trip, which began in late 1899 and extended to June 1900, included a long stay with family friends in Jerusalem, where she threw herself into the study of Arabic, a language in which she would eventually become fluent.16 Highlights of this trip included a side visit to Petra (in present-day Jordan; 29–31 March 1900), a venture up through the Hauran and the Jebel Druze to Damascus (25 April–14 May 1900), and a momentous solo journey to Palmyra in the Syrian desert before returning to Beirut on the Mediterranean coast (15 May–9 June 1900).17

Other Near Eastern trips followed (in 1902 to Haifa and Mount Carmel), and then a particularly ambitious journey in 1905 (January–May). Aimed at ‘wild travel’,18 this trip through Palestine and Syria saw Bell exploring beyond the well-trod paths of tourists, into remoter places, where the well-watered, cultivated fields of the coastal plain gave way to mountains and then the steppe and desert lands of the interior. She retraced some of the earlier steps she had taken in 1900, this time pausing longer in the desert regions around Amman and Damascus, exploring the Jebel Druze at greater length and then moving up through the central part of Syria, taking in the towns and ancient ruined settlements of the Orontes Valley and the rocky hills of the Limestone Massif. She travelled almost entirely independently of other Europeans, escorted only by a small entourage of native guards, guides and a cook.19 Overcoming obstructive Ottoman authorities through her quick wit and abilities in Turkish and Arabic, Bell managed to visit, document and photograph a wealth of peoples and places over the space of four months. The exhilaration she felt in this journey is reflected in her travel account The Desert and the Sown, written upon her return to England, which enjoyed favourable reviews upon its publication in 1907. ‘Charming’20 and ‘enchanting’21 were some of the adjectives used to describe this book, in which nearly every page is filled with colourful descriptions of the people and places she encountered over the course of the journey. Readers were particularly enamoured with her ability to provide ‘snapshots’ of conversations with the people she met, and in so doing present a vivid and often humorous picture of the speakers and their activities, opinions and customs.22 Her accounts described her dealings with people of all occupations and ethnicities, from Turkish officials to shopkeepers, soldiers, shepherds, priests, desert sheikhs, ‘those who sit around our campfires and those who ride with us across deserts and mountains, for their words are like straws on the flood of Asiatic politics, showing which way the streams are running’.23

As one might expect in the writings of an early twentieth-century traveller from Britain, The Desert and the Sown contains an Orientalist undertone in Bell’s description of the peoples of the Near East and her interactions with them. Confident in her intellectual and moral superiority as an Englishwoman, she sometimes characterized Arabs as existing in a perpetually primitive state, petty, impractical, prone to conflict, and unable to progress towards a state of civilization like the West.24 A passage in Bell’s account, describing an ‘Oriental’ as being ‘like a very old child’,25 underscores her patronizing tone. Nevertheless, she also had the capacity to both admire and respect the people she encountered, accepting differences between West and East and, at her best, recognizing the relative nature of value systems, morals and human organization across cultures.26 That she was a woman and thus in some ways marginalized within her own English society may have made her sensitive to attitudes of inequality and difference,27 but it may simply be that as a highly observant individual, her keen recognition and appreciation of human behaviour in its myriad forms often prevailed over other attitudes she might have had about empire, race and gender.

Bell’s 1905 Near Eastern journey had another important aspect: it drew into sharp focus her interest in the antiquity of the regions she passed through. She enjoyed contemplating the cultures and peoples who had been here before her and had left their mark through art, architecture and inscriptions. Archaeology and ancient history are very significant motifs in The Desert and the Sown, taking up almost as much space as her accounts of modern people and places. Her enthusiasm for history is clearly shown in the wealth of ancient sites on her itinerary, including, for example, the Roman site of Baalbek and the impressive Crusader castle of Krak de Chevaliers.28 While many of these sites frequently featured in other tourist itineraries, Bell took the time to explore lesser known sites as well, pausing over their ruins and recalling age, date and cultural significance. Travelling up through central western Syria, for example, she described the high mound of Tell Nebi Mend, the site of the ancient city of Qadesh, and the famous battle fought there between the Hittites and Egyptians, this event also known from hieroglyphs and reliefs in Egypt.29 Beyond Hama, she passed by the ruined Is

lamic castle of Shayzar (which she called Kala‘at Seijar) (Fig. 1.2), describing its impressive situation atop a steep bluff overlooking the Orontes Valley.30 She observed numerous tell sites further along the way (at Sheikh Hadid)31 before arriving at the extensive Greco-Roman site at Qal‘at Mudiq (ancient Apamea), also giving this site ample attention.32 Still further to the north, Bell expressed great excitement at encountering the Princeton archaeological expedition at the Dead City of Tarutin, and she spent the day following them, observing members of the team planning the ruins and deciphering inscriptions. Through their efforts, as Bell relates, ‘the whole 5th century town rose from its ashes and stood before us – churches, houses, forts, rock-hewn tombs with the names and dates of the death of the occupants carved over the door’.33 Clearly, with these site visits and her accompanying descriptions and photographs – the latter often featuring close-up shots of artistic decoration and construction details in the architecture – Bell was beginning to show an archaeological curiosity and knowledge that went beyond the simple attentions of an enthusiastic tourist.

Fig. 1.2 Bell’s 1905 photograph of the Arab castle of Shayzar (tenth to thirteenth centuries CE), overlooking the Orontes River (Syria), with a premodern bridge over the river in the foreground.

Bell’s 1905 journey wasn’t her first to take in archaeological sites and monuments. She had demonstrated a keen interest in the past on earlier occasions, as attested in letters to family members in which she often evocatively described ancient sites and historical details. Bell’s active imagination and romantic nature were frequently at work, envisioning people and events from the past in the places through which she travelled. The landscapes acted as a time portal, too, transporting her back to an age when charismatic or tyrannical kings had ruled, and to lands through which conquering armies had passed. During her stay in Persia back in 1892, she had recalled a stony, desolate valley ringed by mountains, within which stood a Persian temple of death – a ‘tower of silence’ – upon which corpses would once have been laid out to be defleshed by vultures. This ancient structure evoked a grim bygone tradition and the many people who had once witnessed it in their ‘weary journey’ towards death.34 On one memorable trip to Athens with her father in 1899, Bell had the pleasure of meeting the eminent German archaeologist Wilhelm Dörpfeld, and the archaeologist David Hogarth, brother of her Oxford friend Janet. In her letters, Bell burst with enthusiasm over being able to speak with these gentlemen and then holding 6,000-year-old pottery from Melos, exclaiming that her mind reeled at the experiences.35 Later in the same year, while walking through the ruins of Ephesus in Anatolia, Bell imagined St Paul with the shining, gorgeous Greek city in front of him, walking up the colonnaded street and the marble steps to the theatre at the end, just as she had walked.36 She undertook still other archaeologically focussed trips in western Anatolia in 1902: Bell watched with interest as a Byzantine tumulus was excavated at Colophon;37 she made a six-day trip to visit the ancient ruins at Pergamum, Sardis and Magnesia;38 and she observed German excavators digging at Menemen, near Smyrna (Izmir).39

One can sense within her writing that especially in the lands of Palestine and Syria, which she first visited in 1900, she felt a real rapture for ancient places and the striking desert setting in which they were often found. When Bell and her travelling party visited the desert Nabatean city of Petra (29 March 1900), she could not but be stunned by the natural setting, which provided such a magnificent context for the ancient rock-cut tombs (Fig. 1.3), built into the pink sandstone of the desert cliffs and approached through a narrow defile in the rock:

We went on in ecstasies until suddenly between the narrow opening of the rocks, we saw the most beautiful sight I have ever seen. Imagine a temple cut out of the solid rock, the charming facade supported on great Corinthian columns standing clear, soaring upwards to the very top of the cliff in the most exquisite proportions and carved with groups of figures almost as fresh as the chisel left them – all this in the rose red rock, with the sun just touching it and making it look almost transparent. […] We walked about all the afternoon and photographed and were lost in wonder. It is like a fairy tale city, all pink and wonderful, as if it had dropped out of the White King’s dream and would vanish when he woke!40

Bell’s first sight of Palmyra (Fig. 1.4) in the Syrian desert in May 1900 made no less of an impression upon her, the barren surroundings providing the context for the ancient site:

I wonder if the wide world presents a more singular landscape. It is a mass of columns, ranged into long avenues, grouped into temples, lying broken on the sand or pointing one long solitary finger to Heaven. Beyond them is the immense Temple of Baal; the modern town is built inside it and its rows of columns rise out of a mass of mud roofs. And beyond, all is the desert, sand and white stretches of salt and sand again, with the dust clouds whirling over it and the Euphrates 5 days away. It looks like the white skeleton of a town, standing knee deep in the blown sand.41

Fig. 1.3 Bell’s photograph of the rock-cut tomb of Sextius Florentinus (Roman governor of the province of Arabia, 130 CE) at Petra (Jordan) in March 1900.

And yet alongside her taste for lyrical musings over ancient sites, Bell was also acutely interested in the detailed features seen amid the ruins, and willing to take the time to record them in her notebooks. Her writings are filled with such descriptive details, even at Palmyra in 1900:

Fig. 1.4 Colonnade inside the precinct of the Temple of Bel, Palmyra (Syria). Modern mudbrick houses, which in 1900 stood right in the midst of the sacred enclosure, were all subsequently removed.

There is one splendid tower almost perfect, the Kasr el ‘Arus the Arabs call it – the Bride’s Castle. It consists of a great chamber 20 ft high, pilasters running up from floor to ceiling and between them rows and rows of loculi, like so many shelves. When I say the floor I might add that the floor is gone and has left a great pit in the shape of a deep basement, arched over formerly, and also full of loculi. Of the roof of the great chamber about 2/3 remains, elaborately carved, stuccoed and painted, and the colours are still quite fresh. At either end of it was a panel containing 4 portrait heads, I daresay there was one in the middle too, but it had fallen in. Over the door was carved the head of a bearded man, the chief of the family perhaps, and at the opposite end the usual Palmyrene stele, 5 busts in a row on an enormous block of stone with a border round which is always the same, a thing like the body of a chess king at either end and a roll at the top ornamented with wavy lines and low cut wreaths of flowers. We climbed up a broken stair into the next chamber which was much plainer, no carvings in it. There was still another above which we couldn’t get into because the broken floor prevented our reaching the stair. I believe each loculus was closed by a portrait bust of the owner but these have long since been broken or sold.42

Such detailed passages of archaeological features continue in all of Bell’s writings. Moreover, one also observes, particularly from 1905 onwards, the addition of more speculative, scholarly notions, the product of her having learned more about the cultures and artistic traditions of the sites she visited. When describing the site of Baalbek, for example, Bell suggested that it was a ‘combination of Greek and Asiatic genius that produced it and covered its doorposts, its architraves and its capitals with ornamental devices’.43 Bell’s mind was once again speculating on particular architectural traditions when she passed through the ruined Late Antique villages and churches in the hilly region to the northeast of Qal‘at Siman in northern Syria. Not aware that the Princeton archaeological team had previously inspected this region,44 she took it upon herself to carefully inspect the area and offer some explanation for the particular appearance of its architecture, which was ‘not executed by local workmen but by the builders and stone-cutters of Antioch’.45 Such writings reflect the growing confidence with which Bell explored archaeological sites, including those outside the usual tourist itineraries, and her efforts to determine their date and cultural influences.

The improved, scholarly character of Bell’s archaeological visits and her writings by 1905 coincided with her association with Salomon Reinach (1859–1932), an influential European scholar-savant who had entered her life around 1904. Belonging to a German Jewish family and having studied at the University of Paris and the French School in Athens, Reinach was by the turn of the twentieth century a leading expert in Classical languages, the study of mythology and religion, and art history and archaeology.46 His archaeological activities included research in Greece, Asia Minor and French North Africa, the products of which were scores of works analysing Greek and Roman antiquities in these areas. He also wrote prolifically on ancient Gaul.47 As a whole, his publication record was prodigious for its quantity and scope, featuring books and journals that included topics as varied as Greek and Latin epigraphy, Classical and Late Antique art and architecture, the religion of Asia Minor and the Levant, and European medieval and Renaissance art.48

Britain and the Arab Middle East

Britain and the Arab Middle East